African Swine Fever-An “Unprecedented Impact” in the Year of the Pig

News articles continue to point to various market disruptions caused by the ongoing African Swine Fever [ASF] outbreak in Asia and beyond. Today’s update looks at a few of these items in more detail.

Financial Times writers John Reed and Sun Yu reported on Tuesday that, “In the Chinese calendar, this year is the Year of the Pig, a symbol of wealth in China. However, it will be remembered in Asia as the year when ASF devastated hog farming, creating what experts are calling the worst crisis to hit the global livestock and meat industry in decades.

“Since ASF arrived in China in mid-2018, about a quarter of the world’s pigs have died from the disease or culls undertaken to prevent its spread. China farms about half of the world’s pigs and consumes about half the world’s pork.”

“Year of the Pig brings devastation to Asian hog farms,” by John Reed and Sun Yu. The Financial Times (December 17, 2019).

The FT article noted that, “‘We’re talking about unprecedented impact,‘ said Justin Sherrard, global strategist for animal protein at Rabobank. ‘We’re talking about a disease we haven’t seen before at this kind of scale.’

“When ASF spread to south-east Asia this year, it drove up prices of pork and other meats as Asian consumers switched to other sources of protein. Experts say the outbreak will transform farming and the global meat trade well into the 2020s.”

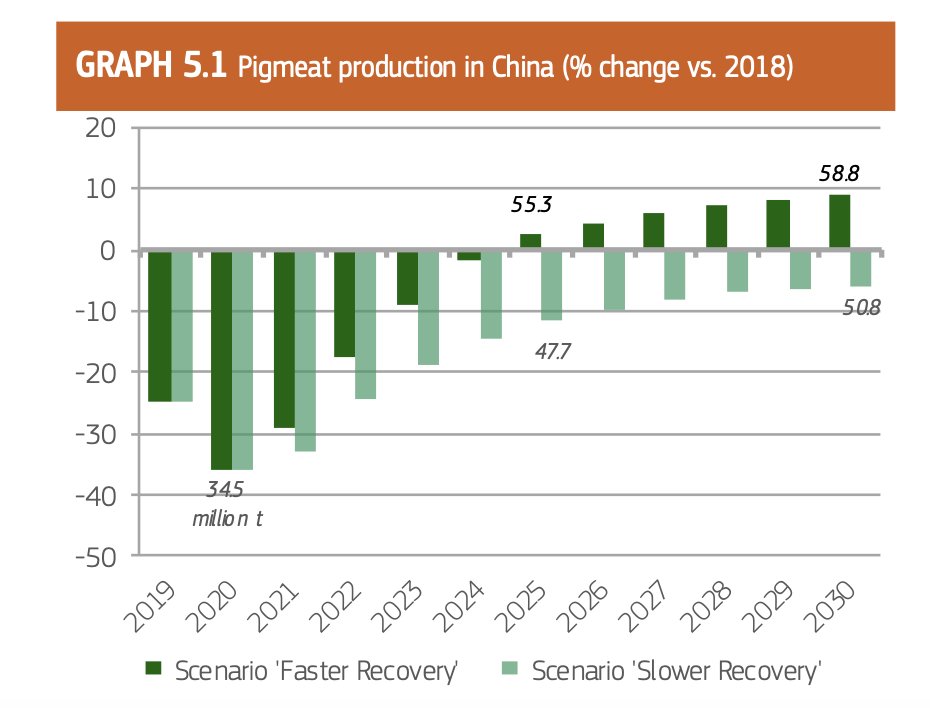

Reed and Yu added that, “Yang Zhenhai, a director at China’s ministry of agriculture, told journalists last month that the government wanted to bring the country’s hog herd back to 80 per cent of its pre-ASF level by the end of 2020. However, analysts think the recovery will take longer.”

“Year of the Pig brings devastation to Asian hog farms,” by John Reed and Sun Yu. The Financial Times (December 17, 2019).

Meanwhile, Reuters writer Gus Trompiz reported last week that, “The African Swine Fever crisis in China and a shift towards plant-based protein in diets could reshape EU agricultural markets over the next ten years, leading to fluctuating pork prices and higher cultivation of pulses and soybeans.”

The Reuters article stated that,

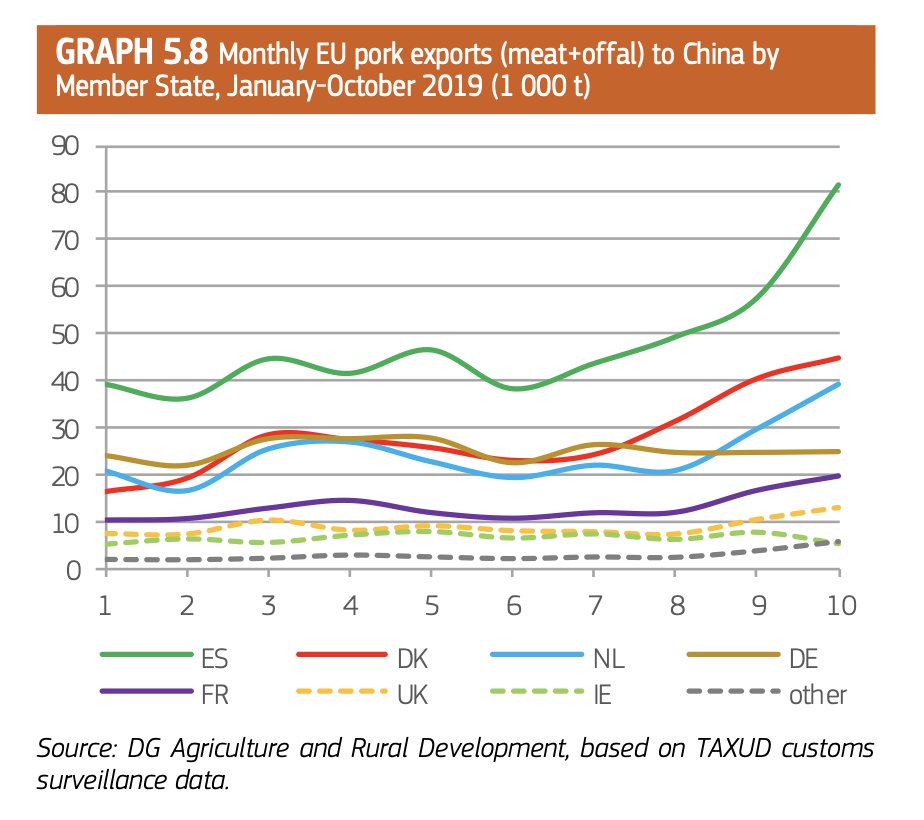

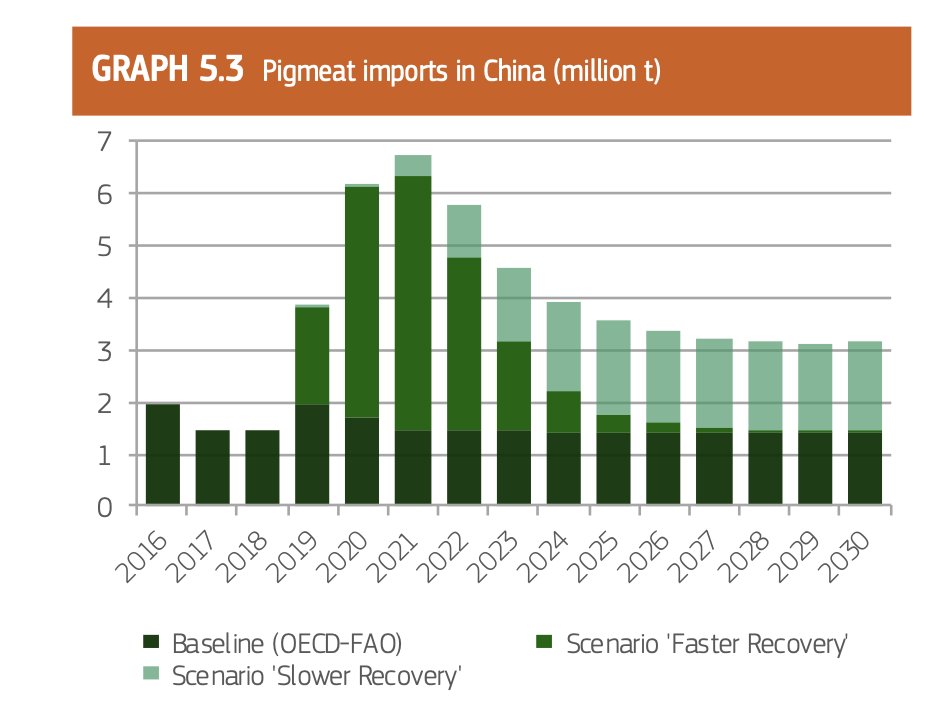

In an agricultural outlook report on [Dec. 10th], the European Commission said annual pork exports from the European Union could peak at more than 4 million tonnes around 2022, depending on the pace of recovery in China’s pig herds, compared with about 2.7 million tonnes last year.

“Pork exports were then seen easing to around 3.4 million tonnes by 2030, still well above volumes before the Chinese ASF outbreak, the Commission said.”

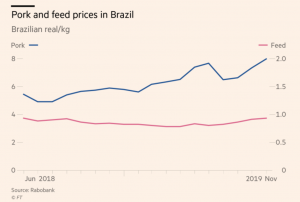

“‘Prices should remain high until Chinese production recovers, and may fall sharply depending on the speed of the recovery and how much the production of EU competitors grows,’ the Commission said, referring to the U.S., Brazil and Canada.”

Some graphs from the European Commission report are included in the Tweets below:

Pigmeat Imports in #China, https://bit.ly/2PxrfBW @EUAgri

* #China’s imports will not stop growing any time soon potentially remaining above pre-ASF levels by 2030 (scenario ‘slower recovery’).

* In 2020, #Chinese pigmeat production may see a record low of 34.5 million t.

* Supply and #pig herd will likely not return to the pre-ASF levels of 54 million t and 440 million heads before 2025 (scenario ‘faster recovery’), https://bit.ly/2PxrfBW

“While an outbreak of African swine fever affects solely pork supplies in China and other Asian countries, a fall in production of that type of meat will drive demand for other products including chicken, said ABPA, which represents pork and poultry producers.”

The Reuters article indicated that, “ABPA forecasts Brazil’s 2020 pork exports may grow by at least 15% next year to 850,000 tonnes. This year exports are estimated to have jumped 14.5% to a projected 740,000 tonnes driven by sales to China, Hong Kong and rising shipments to Russia, Chile and Vietnam.

“Projected Brazilian chicken exports could grow to as much as 4.5 million tonnes next year, a 7% rise from the upper range of 2019 export projections of 4.2 million tonnes, ABPA said.

In a related article regarding American poultry exports to China, Reuters writer Tom Polansek reported that, “Tyson Foods Inc received approval from U.S. and Chinese authorities to export American poultry to China from all 36 of its U.S. processing plants and expects to begin taking orders early next year, a chief supply chain officer for the company said.

U.S. chicken companies are eager to resume sales in China after Beijing last month lifted a nearly five-year ban on imports as Chinese consumers seek pork alternatives. A deadly hog disease has killed millions of pigs and raised meat prices in the pork-loving country.

“Increased Chinese purchases of products like chicken feet, wing tips and legs would help increase U.S. agricultural exports to China as the two countries negotiate a trade deal.”

Mr. Polansek pointed out that, “China is scouring the globe for meat and poultry after African swine fever killed about half of the world’s largest hog herd.”

And on Tuesday, New York Times writers Keith Bradsher and Ailin Tang reported that, “A devastating disease spreading from China has wiped out roughly one-quarter of the world’s pigs, reshaping farming and hitting the diets and pocketbooks of consumers around the globe.

China’s unsuccessful efforts to stop the disease may have hastened the spread — creating problems that could bedevil Beijing and global agriculture for years to come.

“To halt African swine fever, as the disease is called, the authorities must persuade farmers to kill infected pigs and dispose of them properly. But in China, officials have been frugal to the point of stingy, requiring farmers to jump through hoops to seek compensation from often cash-poor local governments.”

The Times article stated that: “The epidemic shows the limits of China’s emphasis on government-driven, top-down solutions to major problems, sometimes at the expense of the practical. It has also laid bare the struggle of a country of 1.4 billion people to feed itself.”

And Bloomberg writers Megan Durisin and Eko Listiyorini reported on Tuesday that, “The deadly African swine fever sweeping across Asia has spread to Indonesia, reaching a region with more than a million pigs.

“Almost 400 backyard farms in Sumatera Utara — a province home to 1.2 million hogs — have been struck by the virus since September, leading to 28,000 pig deaths, the Rome-based World Organization for Animal Health said on Tuesday. While the source of the infection isn’t known, it’s suspected to have spread during the transportation of live animals and may be from contaminated feed or animal handlers.”