Direct Payments Set to Soar in 2019

While producers wait for the USDA to release meaningful information about how MFP 2.0 might impact their farm’s financial projections, we thought it would be helpful to provide context about all forms of direct payments in 2019. Specifically, this week’s post reviews direct farm payment and how the latest round of trade aid will send direct farm payments significantly higher in 2019.

Data and Assumptions

A few comments about the data. First, the USDA’s net farm income projection from March 2019 – the latest data- were used as the baseline for 2019 direct payments and farm income. From this, MFP 2.0 payments for 2019 were assumed to be 2/3 of the total estimate of $14.5 billion, or $9.7. The 3rd round of payments would be paid in early 2020. Of course, the 2nd and 3rd MFP payments are not a guarantee.

The $9.7 billion in MFP 2.0 payments were added to the March 2019 projection of income and direct payments.

Direct Payments

The USDA’s initial projection was for $11.5 billion in direct payments. Readers will remember we noted this was part of an optimistic farm income projection that included higher income with lower direct payments and production expenses. These payments include carryover payment from MFP 1.0 ($3.5b), conservation ($4b), and ARC/PLC payments ($1.7b). With an additional $9.7 billion in MFP 2.0 payments paid in 2019, this would push total 2019 direct payments to $21 billion. Many have emailed and asked if this would be a record for payments.

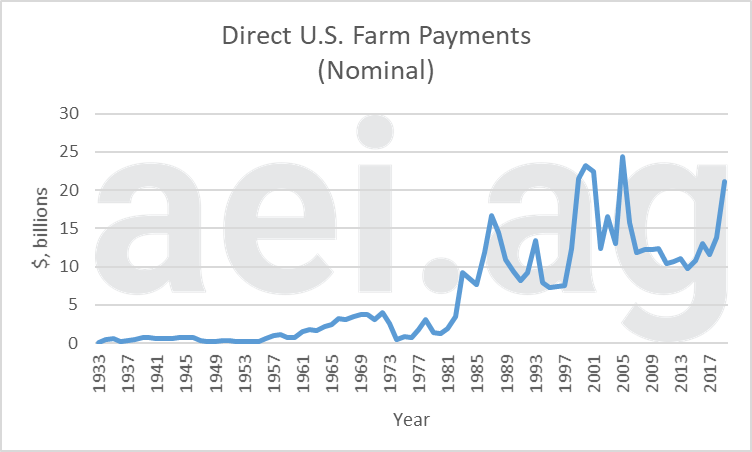

Figure 1 shows annual direct payments since 1933. These data are in nominal terms –not adjusted for inflation. From 2009 to 2018 – the last 10 years- direct payments have averaged $11.5 billion. Furthermore, payments during this period were highest in 2018 at $13.8 billion. This recent history is why the expectation of more than $20 billion in payment in 2019 has been such an eye-popping number.

That said, 2019 is not likely to set a record. In the late 1990s and early 2000 direct payments were exceeded $20 billion 4 times (1999, 2000, 2001 and 2005). In 2005, direct payments reached $24 billion.

Figure 1. U.S. Direct Farm Payments, 1933-2019. Data Source: USDA ERS and aei.ag Calculations.

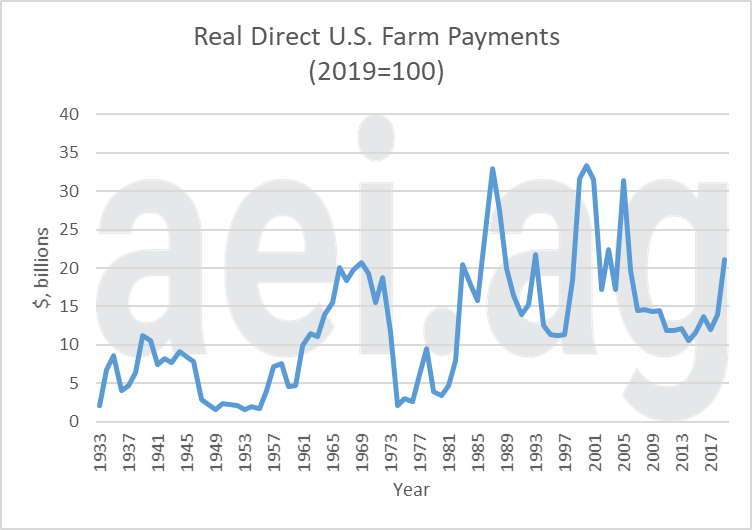

Given the long time series, it’s helpful to consider direct payment data in real – or inflation-adjusted – terms (Figure 2). These data show that direct government spending in the past has exceeded $30 billion in 2019 dollars five times; well above current levels. On the other hand, 2019’s estimate of $21 billion in direct payments has only been exceeded 9 times over the last 87 years. This is to say current levels are historically high but remains below record-high levels.

Figure 2. Real U.S. Direct Farm Payments, 1933-2019. Data Source: USDA ERS and aei.ag Calculations.

Relative to Farm Income

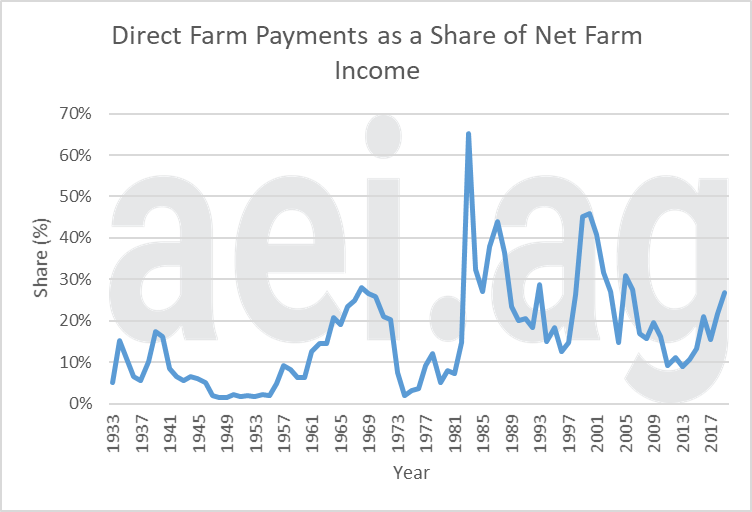

A third way of considering direct farm payments is as a share of sector net farm income (figure 3). Simply put, this measure tells us what percentage of U.S. net farm income came from direct payments.

At the height of the farm economy boom, direct payments accounted for about 10% of farm income between 2011 and 2013. Keep in mind conservation programs – like CRP- are included here. As net farm income fell and the ARC/PLC programs came into play, farm payments have accounted for a growing share of farm income. In recent years, this has been around 20% of farm income. In 2019, direct payments account for 27% of farm income.

Again, we’ve seen direct payments play a much large role in the past. During the farm financial crisis (1983, 1987) and in 1999 & 2000 this measure exceeded 40%. In 1983, when net farm income was dismal, net farm income was 65% of net farm income.

Figure 3. Direct Farm Payments as a Share of Net Farm Income, 1933-2019. Data Source: USDA ERS and aei.ag Calculations.

Direct Payments By Category

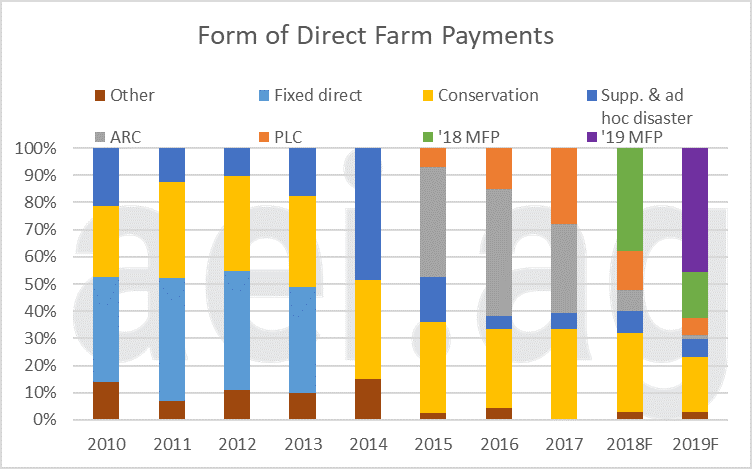

The final way we looked at the data is by type of spending program (figure 4). The only consistent program over the past 10 years has been conservation. Conservation has frequently been 20-30% of total direct farm payments.

Prior to 2014, fixed direct payments were a big share of direct payments. The 2014 Farm Bill phased this program out in favor of ARC/PLC. ARC and PLC spending started in 2015 – the mechanism where payments are made a year after harvest. In 2014, half of direct payments were disaster payments – mostly to livestock producers.

For 2018 and 2019, it’s worth noting how significant MFP payments have been. MFP 1.0 accounted for 38% of 2018 payments and 17% of 2019 payments. MFP 2.0 will account for 46% of all direct payments in 2019 – as well as a significant share of 2020 payments. In total, MFP payments in 2019 (MFP 1.0+ MFP 2.0) will account for 62% of all direct payments made in 2019.

It’s worth pausing to think about what it means when MFP payments are such a large share of direct payments in recent years. Specifically, a majority of 2019 direct payments were funded and authorized outside of new Congressional action and the current Farm Bill. While there isn’t a measure for reviewing how successful a Farm Bill performs, one has to at least consider the possibility that the recently passed 2018 Farm Bill has failed when more than 50% of direct payments were authorized outside of the months-old legislation.

Figure 4. Form of Direct Farm Payments, 2010 – 2019. Data Source: USDA ERS and aei.ag Calculations.

Wrapping It Up

Brent’s recent post on work capital underscores the dire situation facing the farm economy. While Mother Nature’s 2019 supply management plan will likely provide some relief, this alone won’t likely be enough to return net farm income to stable, sustainable levels.

MFP 2.0 will likely push 2019 direct payment above $21 billion, much higher than levels observed in recent memory. That said, direct payments – by many measures- have been higher in the past. Specifically, direct payments exceeded $30 billion – in 2019 dollars- during the 1980s and again in 1999 and 2000.

Looking ahead, one has to wonder how agriculture policy will play out of the next 5 year or so. First, the current Farm Bill – passed in late 2018- is already being bypassed by the USDA and White House with other funding mechanisms. Furthermore, the MFP 2.0 comes after the USDA adamantly spent most of 2018 saying there wouldn’t be further rounds of payments. Both of these realities emphasize the severity of the Trade War and the overall difficult farm economy outlook. A very real possibility is that MFP payments continue for as long as the Trade War continues. While MFP payments have been helpful, the mechanism for allocation and distribution has left a lot to be desired.

Interested in learning more? Follow AEI’s Weekly Insights by clicking here. Also, follow AEI on Twitter and Facebook.

Source: David Widmar, Agricultural Economic Insights