Farmers on Drenched Land Confront Tough Choice on Planting

Millions of farm acres are set to go unplanted with corn this spring as persistent wet weather leaves U.S. farmers facing an agonizing choice: whether or not to risk trying to raise a crop.

Heavy, repeated rains over the past two months have left fields saturated throughout the critical planting period for corn, typically the biggest U.S. crop by acreage. Farmers in rain-soaked states now must decide whether to file insurance claims on unplanted fields, potentially making less money off their farms, switch to less-profitable crops or take their chances sowing corn that may not have time to fully mature.

The inclement weather adds another challenge to a punishing period for farmers, seed and chemical suppliers, and tractor makers. Trade disputes with major U.S. food importers including Mexico and China have cut into crop prices, adding pressure to farm incomes, after several years of bumper harvests swelled global grain supplies.

Each morning over the last week of May, Scott VanderWal climbed into his red Dodge pickup to check whether his fields had dried out enough to plant. Of the 1,300 acres Mr. VanderWal and his family farm near Volga, S.D., only about 600 have been sown. This week, he plans to report an insurance claim for his remaining corn fields, he said.

Under Water

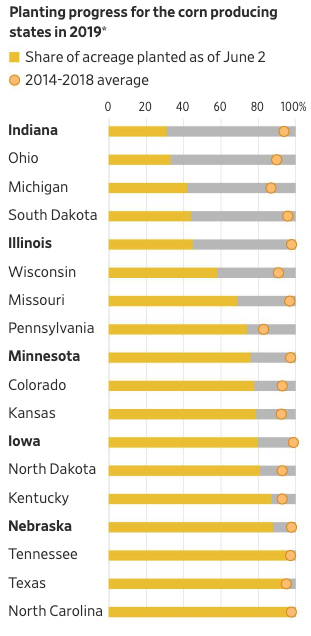

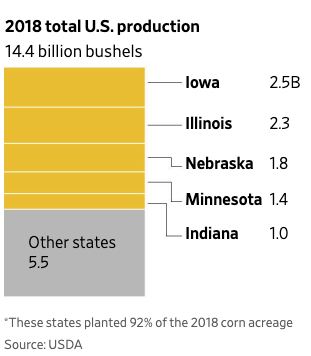

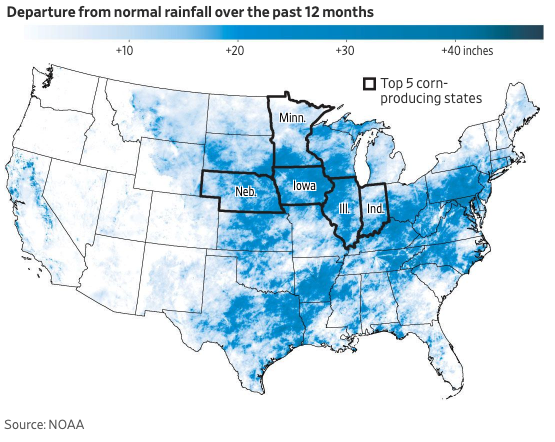

Heavy rains have delayed corn planting nationwide. The top five corn-producing states, in bold below, grew nearly 62% of U.S. corn last year.

“We’re out of time up here,” Mr. VanderWal said as he prepared to till some of his soil with a cultivator to help dry the field.

The wettest 12-month period on record in the continental U.S. means farmers had planted only about 67% of this year’s corn crop by Monday, far below the roughly 96% average by the same date over the previous five years, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture data.

While some farmers may gamble on a late-planted crop that could yield a fraction of a typical harvest, many will turn to crop insurance that pays out when farmers are unable to plant by a preset deadline. Farmers also are weighing the promise of another multibillion-dollar trade rescue package from the USDA, and potential funding from federal disaster recovery legislation. The Trump administration last year directed $12 billion in federal aid toward the U.S. farm sector in response to tariffs on U.S. crops, meat and dairy products.

Farmers this year could seek insurance coverage for between 5 million and 15 million acres that were to be planted with corn, according to grain-market analysts, likely surpassing a record 3.6 million acres of claims on corn acres in 2013.

The American Farm Bureau Federation estimates that 10 million acres of unplanted corn would subtract more than 2 billion bushels of corn production in the U.S., meaning the drenched spring’s impact on grain prices and farmers’ income could linger.

Agribusinesses specializing in corn refining, including Archer Daniels Midland Co. and Bunge Ltd. , said last month that flood damage took a sizable bite out of their first-quarter earnings. ADM profits sank by $60 million due to damage to plants and logistics problems created by the flooding.

The wet weather and delayed planting is also pushing up crop prices. After hitting their lowest point in a year in mid-May, corn prices climbed 24% through the rest of the month. Soybean prices gained 11% in the same time period. That isn’t expected to trickle down to higher food prices for consumers right away because huge stores of crops have piled up recently due to bumper harvests and trade disputes in recent years.

Farmers had planted only about 67% of this year’s corn crop by Monday. PHOTO: NATI HARNIK/ASSOCIATED PRESS

But the rising grain prices have weighed on shares of meatpackers including Sanderson Farms Inc. and Pilgrim’s Pride Corp. , which could see higher prices more immediately for the soybeans and corn they feed to livestock. Shares in Sanderson and Pilgrim’s Pride are down 9% and 8% respectively over the past month.

Time is running short for farmers to claim and collect on insurance policies. Farmers in the northwestern corn belt had a deadline of May 25 to file such claims, while those in Iowa, the biggest corn-producing state, needed to file by May 31. In Illinois, Indiana, Ohio and Michigan, the deadline is Wednesday.

If farmers don’t file a claim by those dates, the revenue their coverage guarantees decreases by 1% each day while they judge their chances of planting a successful crop. Farmers must often report a claim within 20 days of the cutoff date.

Doug Dozier, a claims supervisor in Illinois for crop insurer Country Financial, estimated that the number of claims handled by his office this spring is running at least double the normal level.

Such insurance coverage usually doesn’t match what a farmer would make growing an average crop. For an acre that would have yielded roughly $800 growing corn this year, a typical prevented-planting insurance policy would pay approximately $368, according to estimates from the University of Illinois.

The inclement weather adds another challenge to a punishing period for farmers, seed and chemical suppliers, and tractor makers. PHOTO: DANIEL ACKER/BLOOMBERG NEWS

For farmers like Mark Tuttle, who raises corn and soybeans in northern Illinois, such coverage has become the only option. Mr. Tuttle said his land has been too wet to plant any of his 1,000 acres of farmland, save for a few acres of winter wheat.

“There’s nothing here, and I have many neighbors that have nothing planted,” he said.

Planting when the ground is too wet or saturated can smother seeds that need oxygen to germinate. Wet soil also can rot emerging crops and form a crust too tough for sprouts to break through.

Even if farmers get a late crop in the ground, corn may not fully mature by the time the fall’s first frost hits, producing yields one-fifth or more below the norm, according to agricultural economists.

U.S. Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue said this week that the agency is evaluating whether a planned $16 billion bailout package for farmers facing lower crop prices because of tariffs also could be used to provide relief to weather-stricken farmers.

The USDA hasn’t set the final parameters of that aid.