Has Cattle Herd Expansion Ground to a Halt?

Normally, at this time of year, the Cattle industry focuses on information contained in the USDA’s January 1 estimates of the U.S. cattle herd. The inventory report provides a wealth of information to market participants including estimates of the all cattle and calves inventory, and both the beef and dairy cow inventories as well as an estimate of the prior year’s calf crop. This year, however, USDA extended the data collection period because of the government shutdown and the inventory estimates will be provided as of January 31, instead of January 1, with the report scheduled for release on February 28. As a result, we’re left to speculate regarding what information the report might contain.

Normally, at this time of year, the Cattle industry focuses on information contained in the USDA’s January 1 estimates of the U.S. cattle herd. The inventory report provides a wealth of information to market participants including estimates of the all cattle and calves inventory, and both the beef and dairy cow inventories as well as an estimate of the prior year’s calf crop. This year, however, USDA extended the data collection period because of the government shutdown and the inventory estimates will be provided as of January 31, instead of January 1, with the report scheduled for release on February 28. As a result, we’re left to speculate regarding what information the report might contain.

U.S. cow-calf producers have been expanding the size of their herds since 2014, when the all cattle and calves inventory bottomed out at 88.5 million head. A year ago this time the all cattle and calves inventory stood at 94.4 million head, nearly 7% larger than 4 years earlier. So, what happened to the size of the herd in 2018? Did U.S. producers continue to increase their herds in 2018 or did expansion grind to a halt?

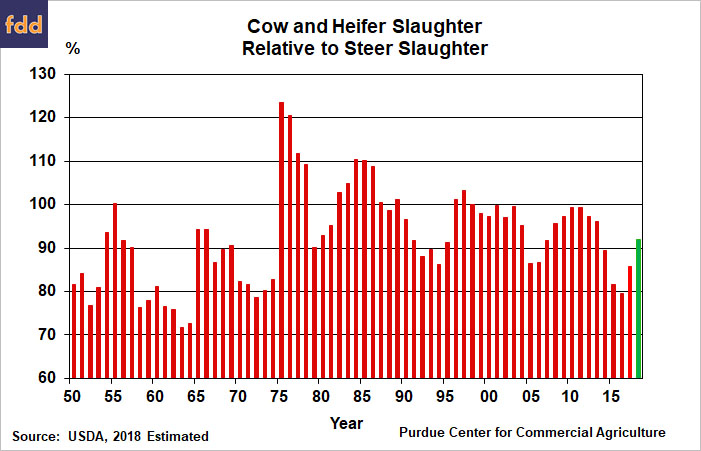

One of the best long-term indicators regarding the expansion or contraction of the cattle herd is the ratio of female slaughter (cows and heifers) to steer slaughter. During expansionary phases female slaughter declines relative to steer slaughter as producers hold back females to expand their herds. When expansion starts to slow or producers shift into herd liquidation, female slaughter increases relative to that of steers. Let’s take a look at the recent data to see if it conforms to this pattern.

In 2013, the most recent year of herd liquidation, female slaughter as a percent of steer slaughter was relatively high at 96%. When expansion got underway female slaughter began falling, declining to 89% in 2014. Female slaughter fell even more sharply the next two years as herd expansion accelerated. For example, in 2015 the ratio was 82% and in 2016 the ratio was 80%. The first sign that the industry’s expansion phase was slowing down appeared in 2017 when the ratio of females to steers in the slaughter mix rose to 86%. What was the ratio in 2018? Based upon USDA’s weekly slaughter estimates, female slaughter as a percentage of steer slaughter rose to about 92% during 2018. The implication is that expansion during 2018 did indeed come to a halt, but it does not look like the industry shifted into a liquidation phase. Instead, the odds appear to be quite high that the size of the nation’s cattle herd remained essentially unchanged during 2018. What does that mean for future beef supplies and prices?

Commercial beef production in the U.S. during 2018 totaled 26.9 billion pounds, about 2.6% more than a year earlier. But per capita beef supplies at 57 pounds were virtually unchanged from 2017, largely because of a small improvement in beef exports combined with a modest decline in beef imports. Commercial beef production appears likely to rise in 2019, but improvements in foreign trade could offset the modest production increase once again, leaving domestic per capita supplies unchanged for the second year in a row.

USDA’s 5-Market average price for fed steers last year was about $117 per cwt. With little change in beef supplies expected this year, fed steer prices are likely to average near their year ago level. Prices for 500-600 pound steers in Kentucky averaged about $154 per cwt. in 2018, up 3% compared to a year earlier when they averaged $149 per cwt. Prices in early 2019 started the year off weaker than 12 months earlier, averaging just $135 per cwt. during January. Widespread losses by cattle feeders during the last half of 2018 weakened feeders’ demand for calves, as did severe winter weather in January, as they attempt to purchase calves and feeders that generate more attractive breakeven prices. Calf prices in Kentucky this upcoming year are expected to average below 2018’s average, but the decline in the annual average is likely to be smaller than what took place in January. Look for Kentucky steer calves to average in the $140s during 2018, assuming no significant crop production problems that would push feed grain prices up substantially this summer and fall.

Source: James Mintert, Farmdocdaily