RaboBank-Ten-year Outlook for U.S. Grains and Oilseeds Looks Challenging

Our grain & oilseed baseline outlook to 2028 indicates that prices and farmer margins will remain under pressure. There are many factors influencing our long-term projections (a series of papers on specific crops and topics will follow this article). Trade and sector disrupters, including Chinese tariffs on US agricultural products and the African swine fever (ASF) outbreak in China, weighed heavily on prospects. These two factors alone will drive down US soybean exports on average by around 200m bushels annually, when compared to levels in 2017 (prior to the tariffs and ASF). Also, the gloomy economic outlook and the strengthening of the US dollar provide additional challenges for US grain & oilseed exports, which are needed to balance the market.

The future of ethanol and biofuels continues to be challenging. Despite the decline in corn prices, ethanol demand is expected to remain flat in the near term, with some weakening in the mid- to long-run, as more gas-efficient (as well as electrical and hybrid) cars are expected to enter into the market.

During the next decade, our results indicate that animal feed is expected to grow, as animal production will continue to expand in North America. Provided it stays on top of disease prevention, the US meat industry (along with Europe and Brazil) is likely to fill the protein gap that is widening in some geographies as a result of disease outbreaks, such as ASF in Asia. Long-term demand for corn dried distillers’ grain is positive, as the number of cattle in the US and Mexico is anticipated to grow. Poultry production will continue to grow and, together with pork production, should provide support to corn, soybean, and soymeal demand.

What Is Next?

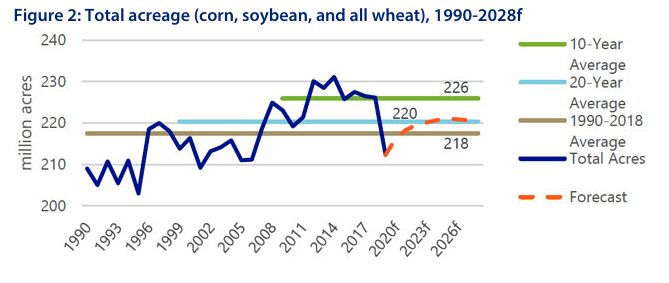

Low prices. Given current conditions, we anticipate corn prices to move to the low- to mid-range of USD 3/bu, while soybeans will struggle to break above USD 9/bu (see Figure 1). All wheat may find some stability at USD 5/bu levels.

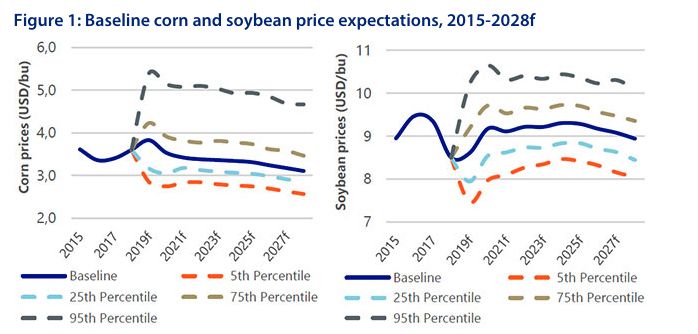

Given the current demand and price expectations, our baseline results indicate that US farmers will reduce and recalibrate acreage. Over the next decade, we anticipate acreage (soybeans, corn, and wheat) to stabilize at around 220m acres, down from an average of 227m from 2014 to 2016/17, and still 3m below the USDA’s March 2019 prospective plantings (see Figure 2). On average, the 7m-acre reduction will come mostly from soybean areas equal to the amount of export that would have gone to China under normal conditions – a result of the loss of access to Chinese markets.

Despite this reduction, and as we move to 2028, we anticipate the US grain & oilseed market to remain off-balance, as yields will continue to improve, and production will outpace demand. Just to illustrate, we expect soybean annual stocks to average above 750m bushels, which is four times the volume the industry stored annually on average over the last ten years. This will create tremendous challenges for farmers, elevators, and the current infrastructure.

The US Farming Model Needs to Change

In order to increase economies of scale, we expect to see continued consolidation in US farming. However, this strategy alone won’t guarantee success in the long run. Farming practices and the traditional model need to change. Current practices will leave US farmers heavily exposed to a highly commoditized market, where margins are expected to be under severe pressure. New farming practices could include boosting cooperation among farmers and players, for example buying in bulk or optimizing machinery and equipment while eliminating excess capacity.

For commodity production, the distinction between the most and least profitable enterprises is less focused on productivity (yield) and more broadly defined by lower cost per acreage of production and better marketing strategy. Our research has shown that scale can offer lower machinery costs, by as much as USD 50/acre. An increasingly viable option for operations looking to seek scale is greater allocation of capital to acreage over machinery, while looking to increase the use of custom applications and outsourced field work. This operating model offers the farmer greater access to increased data, technology, and modern farm equipment. Greater acreage also offers greater purchasing power of inputs (i.e. seeds, crop protection, and fertilizers). Input providers would always rather sell to a smaller operation than a big operation. The difference in the cost of inputs per acre between a 1,000-acre operation and a 2,500-acre operation can be as much as USD 25/acre, which, increment upon increment, changes the landscape of a farmer’s income.

At the end of the day, farmers need to adjust practices to keep their heads above water, and some of the best and most efficient farming operations came through the tough lessons learned in the 1980s. Farmers need to adapt to the options out there, whether that is scaling, changing practices, or adopting new technologies. Consumer trends and data-driven traceability offer farmers and end processors greater collaborative power today than they’ve had in the past. Should farmers be looking to bypass the middle man and grow to the specifications of end processors? Should farmers look to ‘de-commoditize’ their production to move into a value-added sphere? Nothing should be beyond the realm of consideration for farmers as we move forward.

Don’t Miss

In the weeks to come, RaboResearch will release a series of reports, wherein we will get deeper into the main drivers and prospects of the grain, oilseed, and animal protein markets and will evaluate different scenarios.

Source: Rabobank