Reviewing the Trade War Consequences and Impacts

As the bitter reality of a seemingly never-ending (and possibly expanding) trade war crashes down on the farm sector it’s useful – albeit sobering – to think about the economic consequences and impacts.

Exports

Although it’s hard to say exactly when the Trade War with China began, the U.S. farm economy has clearly felt its impacts. The most notable of these impacts began officially in July 2018 when China imposed a 25% retaliatory tariff on soybeans imported from the U.S.

However, the reach of the Trade War extends well beyond soybeans. For reference, the value of total U.S. exports to China in 2017- pre-Trade War- was nearly $130 billion. Ag exports accounted for about 15% of total U.S. exports to China that year.

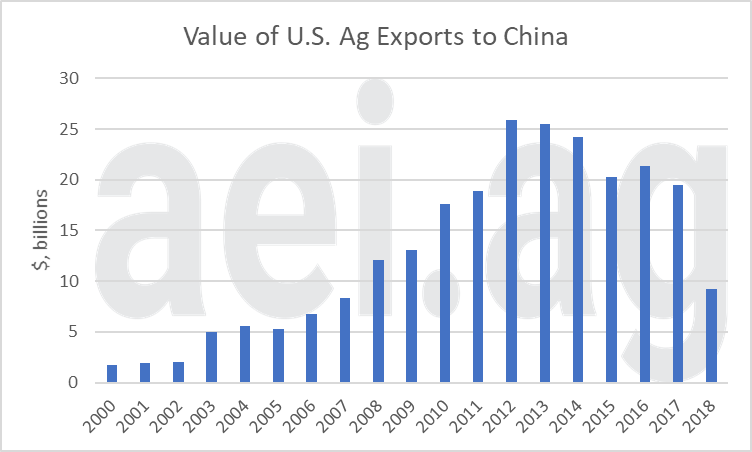

Figure 1 shows the value of annual U.S. ag exports to China since 2000. As we noted in an earlier post, the chart shows two stories: the boom in ag exports during the farm economy expansion, and the trade war impact. From the early 2000s to 2012/2013, exports to China increased an incredible pace. Weak commodity prices from 2014 to 2017 translated in a lower value of exports to China (one of the challenges of using the value of exports to measure activity).

Take note at the change from 2017 to 2018. The value of total ag exports to China in 2017 was roughly $19 billion. In 2018, ag exports to China fell by more than 50%, to $9 billion. Thinking about 2019, one has to wonder how low the value of ag export to China might fall should the trade war last through the full calendar year.

Figure 1. Value of Total U.S. Ag Exports to China, 2000 – 2018. Data Source: USDA GATS.

Figure 1. Value of Total U.S. Ag Exports to China, 2000 – 2018. Data Source: USDA GATS.

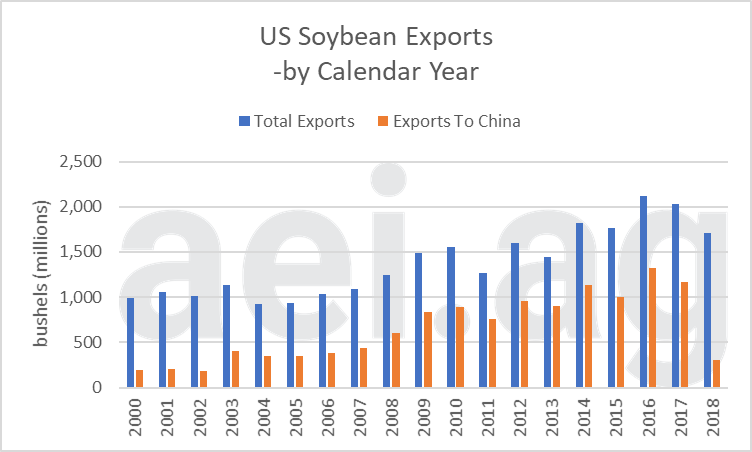

Soybeans have gotten much of the attention in the Trade War because China is such an important market for soybeans. Figure 2 shows two measures of soybean exports- total bushels exported (in blue) and bushels exported to China (in orange). Pre-Trade War, soybean export to China had been at or above 1 billion bushels annually since 2014. Since 2009, China has accounted for over one-half of all U.S. soybean exports. In 2018, exports to China fell to 300 million bushels, levels last observed pre-2003. The change from 2017 to 2018 was a 74% decline.

While the U.S. increased exports to other countries, total export activity slumped since the Trade War began. After 2+ billion bushels of exports in 2016 and 2017, total soybean exports in 2018 were 1.7 billion bushels, a 16% decline from 2017.

The sharp contraction in soybean export certainly has the makings of an adverse demand shock. The question is how long this will be sustained.

Figure 2. U.S. Soybean Exports, Total (in blue) and to China (in orange), 2000- 2018. Data Source: USDA GATS.

Commodity Prices and Outlook

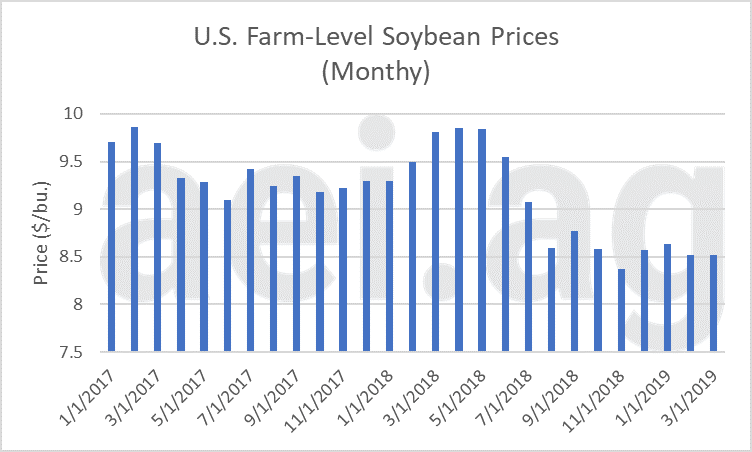

Figure 3 shows the average monthly price farmers received for their soybeans sold. As the realities of the Trade War and a large U.S. soybean crop became evident, soybean prices fell from the $9.50/bushel (and higher) prices in the spring to roughly $8.50 per bushel since August 2018.

Figure 3. U.S. Farm-Level Soybean Prices. Monthly. Jan 2017- March 2019. Data Source: USDA GATS.

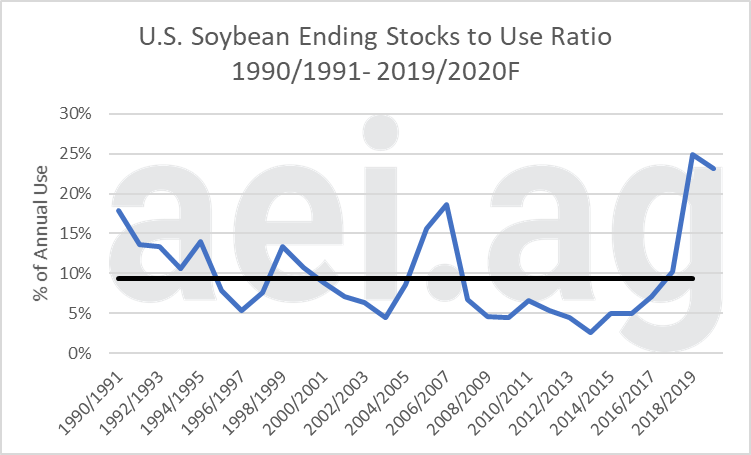

Low soybean prices are a reflection of burdensome ending stocks. Figure 4 shows U.S. soybean ending stocks relative to use since 1990/1991. While the stocks-to-use ratio was averaged about 9% over the time period, stocks are currently well above those levels. For the crop harvested last fall (the 2018/2019 marketing year), stocks are at 25% of use. For the crop being planted now (2019/2020 marketing year), the current forecast is for a stocks-to-use ratio of 23%. To put this in perspective, prior to the Trade War, U.S. soybean stocks exceeded 20% of use only three times since 1960.

Figure 4. U.S. Soybean Endings Stocks to Use Ratio, 1990/1991 to 2019/2020. Data Source: USDA PSD. Average from 1990/1991 – 2018/2019 – 9.3%. 2019/2020F: 23.1%.

It’s certainly hard to argue the Trade War impacts on corn were a penny a bushel – the 2018 MFP payment rate- when the indirect impacts are considered. This is to say that producers were likely to plant more acres of corn given the bleak soybean outlook. When the prices of one commodity are depressed this has a way of working into other commodities. This is essentially what we have been arguing about wheat for some time. Low prices of wheat have set off a search for alternatives, thereby lowering prices of other commodities. Now soybeans are playing that role.

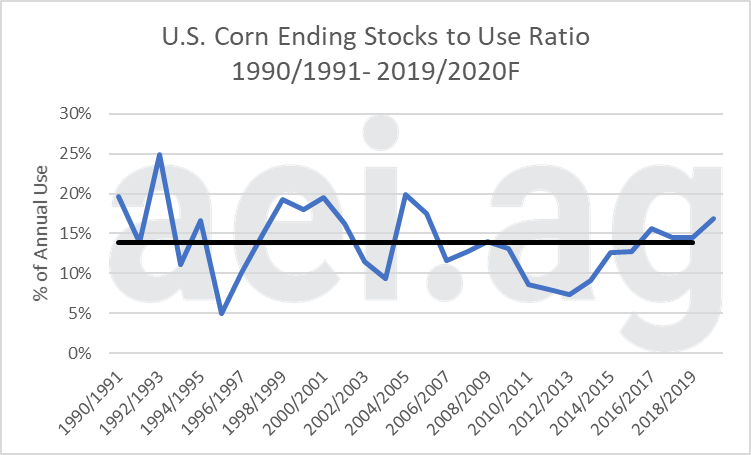

Figure 5 shows the USDA’s forecasted corn stocks-to-use ratio for 2019/2020. While corn had been maintaining stocks near the average of 14%, the current forecasts – due to a large uptick in acres planted- is that corn ending stocks could approach 17% of use. If realized, this would be the highest level since the early 2000s. This is, of course, before the impact of the terrible planting season has been accounted for, but the weather causing this is clearly independent of the trade war.

The reality of the situation is that the poor soybean prices – and returns – lead producers to plant alternative crops; effectively pushing soybeans’ problems onto corn, wheat, and other crops.

Figure 5. U.S. Corn Endings Stocks to Use Ratio, 1990/1991 to 2019/2020. Data Source: USDA PSD. Average from 1990/1991 – 2018/2019 – 13.9%. 2019/2020F: 16.9%.

Farm Income

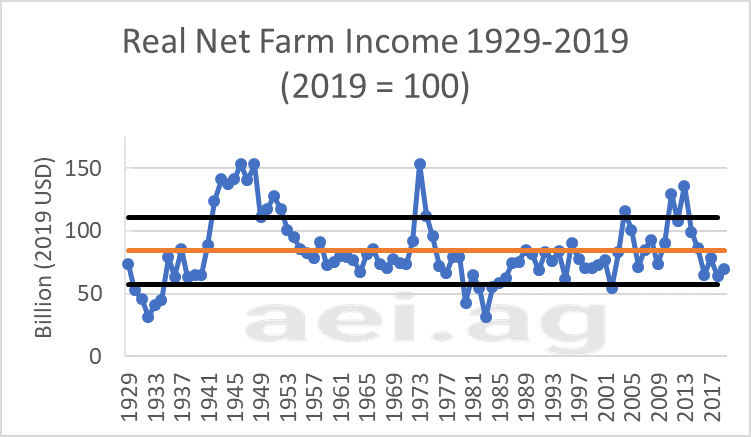

There is no way around it, the farm economy is struggling. After coming off the boom-era highs, aggregate net farm income since 2016 has been lousy (figure 6). Farm income in 2018 was $64 billion, the lowest in recent years. This was even with $5.2 billion of the 2018 MFP payments being allocated to the 2018 calendar year.

Some comfort can be taken from the fact that farm income hasn’t fallen to levels observed and sustained during the farm financial crisis of the 1980s. However, farm income since 2016 has been painfully low and is at levels that erode farm financial conditions. U.S. net farm income is a long way from the $80 billion – or so – that will be needed to provide stability. Furthermore, it’s doesn’t seem like we’ll get there in 2019.

Figure 6. Real Net Farm Income, 1929 – 2019 (2019 = 100). Data Source: USDA’s ERS.

The Big Picture

Colleagues at Purdue University last summer conducted research looking at the big-picture impacts of the 25% tariff China placed on U.S. soybeans. This research used what is known as a general equilibrium model and considers alternative scenarios. It’s important to recognize that this work is not a forecast about the future, but provides a method for us to measure the impacts of the single event.

Those interested in the details can read more here. Below are six key summary points:

1.) U.S. soybean exports to China fall substantially, but did not go to zero. Their research estimates the decline to range from 48% to 91% lower.

2.) Total U.S. soybean exports fall. The rest of the world will not make up for all the losses to China.

3.) China’s total imports of soybeans decreases.

4.) U.S. soybean production declines, between 11% to 15%.

5.) Brazilian production of soybeans increases by 9% to 15%.

6.) Brazil is the only one that wins. Economic losses for the U.S. ($2.2 to $2.9 billion annually) and China ($1.7 to $3.4 billion annually) come for a gain to Brazil, which has an uptick in economic well being of $1.5 – $2.8 billion annually.

Wrapping it Up

The impacts of the Trade War are in the farm economy are substantial. The recent announcement of another round of trade aid to U.S. producers will provide some help. However, the details of the program are to date unknown and perhaps a moving target. While the government payments will provide some relief they will not solve all of the problems that have been created by the trade war. Exacerbating the problem would be an outbreak of tariffs with Mexico – which is where we seem to be headed.

Combined with strong soybean production in 2017 and 2018, the U.S. is facing burdensome ending stocks, low commodity prices, and weak farm income. China is by far the world’s most important importer of soybeans and an important market for a number of other agricultural commodities.

Without Chinese purchases, it will be very difficult to shrink the soybean balance sheet without significantly fewer acres and/or a crop failure. Without a crop failure, this will almost certainly be accomplished through soybean prices that are low enough so as to discourage production.

Looking a bit longer term, the prospects of a continuing Trade War with China — one that lasts beyond 2019 – have seemingly increased. If this happens, the impacts on U.S. agriculture will be profound. The lower prices that would be required to shrink soybean acres, would result in producers significantly increasing acres of other crops, most notably corn. As one might expect, that will also have negative impacts on corn prices.

At this point, there is great uncertainty about the Trade War(s), but also regarding the prospects for crop yields in 2019. The presence of this potential supply shock is helping to mitigate the negative demand shock associated with the Trade War. How long either last is uncertain at this point. We can only hope that the Trade War(s) would find resolution sooner rather than later. If it lasts beyond this year, the government will have to be prepared to deal with again making major trade aid payments or seeing the agricultural economy sink.

Source: Brent Gloy and David Widmar, Agricultural Economic Insights